Originally published at https://www.cio.com/article/4028051/designing-for-humans-why-most-enterprise-adoptions-of-ai-fail.html

Building technology has always been a messy business. We are constantly regaled with stories of project failures, wasted money and even the disappearance of whole industries. It’s safe to say that we have some work to do as an industry. Adding AI to this mix is like pouring petrol on a smouldering flame — there is a real danger that we may burn our businesses to the ground.

At its very core, people build technology for people. Unfortunately, we allow technology fads and fashions to lead us astray. I’ve shipped AI products for more than a decade — at Workhuman and earlier in financial services. In this piece, I will take you through hard-earned lessons I’ve learned through my journey. I have laid out five principles to help decision-makers — some are technical, most are about humans, their fears, and how they work.

5 principles to help decision makers

The path to excellence lies in the following maturity path: Trust → Federated innovation → Concrete tasks → Implementation metrics → Build for change.

1. Trust over performance

Companies have a raft of different ways to measure success when implementing new solutions. Performance, cost and security are all factors that need to be measured. We rarely measure trust. Unfortunate, then, that a user’s trust in the systems is a major factor for the success of AI programs. A superb black-box solution dies on arrival if nobody believes in the results.

I once ran an AI prediction system for US consumer finance at a world-leading bank. Our storage costs were enormous. This wasn’t helped by our credit card model, which spat out 5 TB of data every single day. To mitigate this, we found an alternative solution, which pre-processed the results using a black-box model. This solution used 95% less storage (with a cost reduction to match). When I presented this idea to senior stakeholders in the business, they killed it instantly. Regulators wouldn’t trust a system where they couldn’t fully explain the outputs. If they couldn’t see how each calculation was performed every step of the way, they couldn’t trust the result.

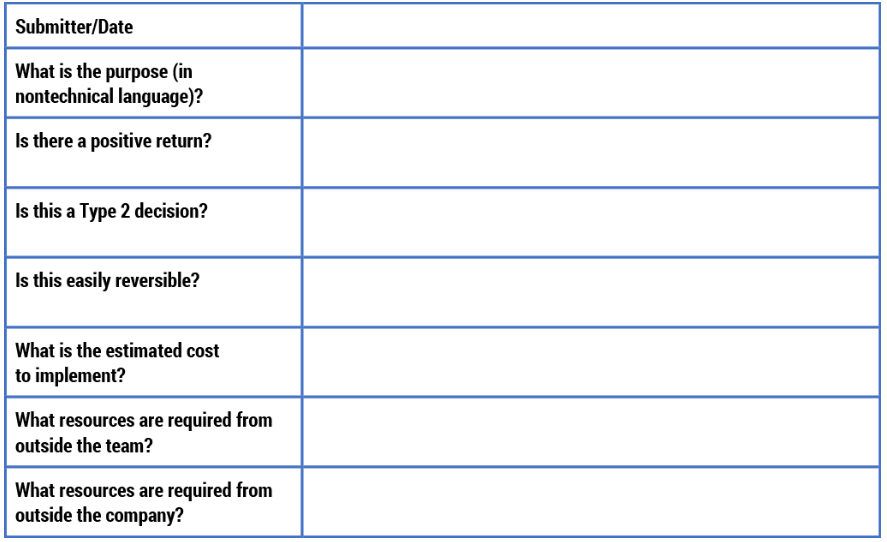

One recommendation here is to draft a clear ethics policy. There needs to be an open and transparent mechanism for staff and users to submit feedback on AI results. Without this, users may feel they cannot understand how results are generated. If they don’t have a voice in changing ‘wrong’ outputs, then any transformation is unlikely to win the hearts and minds needed across the organisation.

2. Federated innovation over central control

AI has the potential to deliver innovation at previously unimaginable speeds. It lowers the cost of experiments and acts as an idea generator — a sounding board for novel approaches. It allows people to generate multiple solutions in minutes. A great way to slow down all innovation is to funnel it through some central body/committee/approval mechanism. Bureaucracy is where ideas go to die.

Nobel-winning philosopher F. A. Hayek once said, “There exist orderly structures which are the product of the action of many men but are not the result of human design.” He argued against central planning, where an individual is accountable for outcomes. Instead, he favoured “spontaneous order,” where systems emerge from individual actions with no central control. This, he argues, is where innovations such as language, the law and economic markets emerge.

The path between control and anarchy is difficult to navigate. Companies need to find a way to “hold the bird of innovation in their hand”. Hold too tight — kill the bird; hold too loose — the bird flies away. Unfortunately, many companies hold too tight. They do this by relying too heavily on a command-and-control structure — particularly groups like legal, security and procurement. I’ve watched them crush promising AI pilots with a single, risk-averse pronouncement. For creative individuals innovating at the edges, even the prospect of having to present their idea to a committee can have a chilling effect. It’s easier to do nothing and stay away from the ‘large hand of bureaucracy’. This kills the bird — and kills the delicate spirit of innovation.

AI can supercharge innovation capabilities for every individual. For this reason, we must federate innovation across the company. We need to encourage the most senior executives to state in plain language what the appetite is for risk in the world of AI and to explain what the guardrails are. Then let teams experiment unencumbered by bureaucracy. Central functions shift from gatekeepers to stewards, enforcing only the non-negotiables. This allows us to plant seeds throughout the organisation, and harvest the best returns for the benefit of all.

3. Concrete tasks over abstract work

Early AI pioneer Herbert Simon is the father of behavioral science, a Nobel and Turing Prize winner. He also invented the idea of bounded rationality. This idea explains that humans settle for “good enough” when options grow beyond a certain number. Generative AI follows this approach (possibly because it is trained on human data, it mimics human behaviour). Generative AI is stochastic — every time we give the same input, we get a different output — a “good enough” answer. This is very different from the classical model we are used to — given the same input, we get the same output every time.

This stochastic model, where the result is unpredictable, makes modelling top-down use cases even more difficult. In my experience, projects only clicked once we sat with the users and really understood how they worked. Early in our development of the Workhuman AI assistant, generic high-level requirements gave us very odd behaviors and was unpredictable. We needed to rewrite the use cases as more detailed, low-level requirements, with a thorough understanding of the behaviour and tolerances built in. We also logged every interaction and used this to refine the model behaviour. In this world, general high-level solution design is guesswork.

Leaders at all levels should get closer to the details of how work is done. Top-down general pronouncements are off the table. Instead, teams must define ultra-specific use cases and design confidence intervals (e.g., “90 % of AI-produced code must pass unit tests on first run”). In the world of Generative AI, clarity beats abstraction every time.

4. Adoption over implementation

Buying a tool is easy; changing behaviour is brutal. A top-down edict can help people take the first step. But measuring adoption is the wrong way to drive change – instead, it gives box-ticked “adoption” but shallow, half-implemented usage.

Executives are every bit as much the victims of fads and fashions as any online shopping addict (once you substitute management methods, sparkling new technologies and FOMO for the latest styles from Paris). And it doesn’t take artificial general intelligence to notice that the trend for AI is hot, hot, hot! Executives need to tell an AI story and show benefits, as they are under pressure from shareholders, investors and the market at large. Through my network in IASA, I have broadly seen this result in edicts to measure “AI adoption”. Unfortunately, this has had very mixed results so far.

Human nature abhors change. A good manager has a myriad of competing concerns, including running a group, meeting business challenges, hiring and retaining talent and so on. When a new program to adopt an AI strategy comes down from executives, the manager — who is trying to protect their team, meet the needs of the business and keep their head above water — will often compromise by adopting the tooling, but failing to implement it thoroughly.

At Workhuman, we have found that measuring adoption (and not only for AI) is not the right way to begin a transformation. It measures the start of the race, but ignores the podium entirely. Instead of vanity metrics, when we measure success, we measure outcome metrics (e.g. changed work process, manual steps retired and business drivers impacted). By measuring implementation and impact, we avoid the ‘box-ticking’ trap that so many companies fall into.

From our decade-plus experience in AI, we have also understood that AI transformation is part of a bigger support system, including education, tooling and a supportive internal community. We partnered with an Irish university to run diploma programs in AI internally, and provide AI tooling to all staff, whatever their role. We have also fostered internal communities at all levels to help drive understanding. This has helped us as we deliver AI solutions, both internally and externally, as shown by the release of our AI Assistant, a transformational AI solution for the HR community.

5. Change over choice

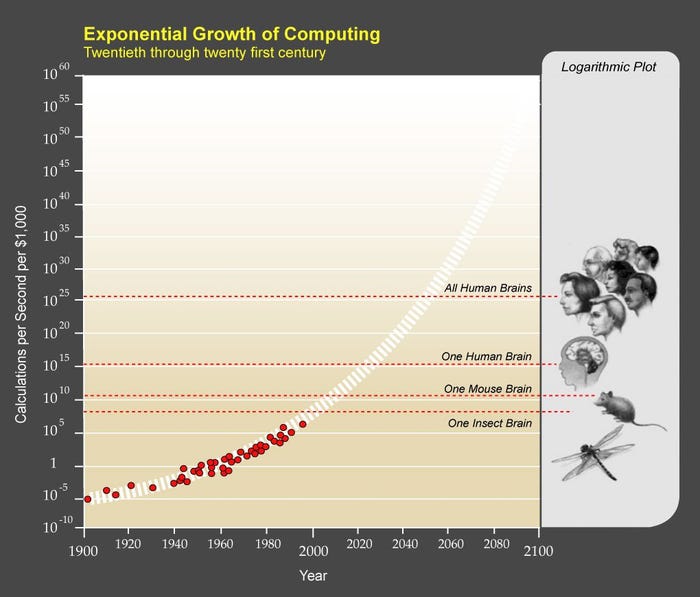

The AI landscape shifts monthly, with a continual flow of new models and vendors locked in a constant race. A choice that locks you into a single technology stack could have your company resembling a horse and buggy clip-clopping through the center of a modern city in the near future.

When we began looking at models for our new AI assistant, we faced several challenges. First off, what can each model do? There were few useful benchmarks, and those that existed offered little in the way of business capability insights. We also struggled to measure how the various strengths weighed up against other models’ weaknesses and vice versa.

Eventually, we agreed on one core architectural principle — everything we design must be swappable. In particular, we must be able to change the core foundation models that underlie the solution. This has allowed us to adjust continually over the last year. We test each new model after release, and work out how each one can be best used to give a great experience to our customers.

Because models are changing so fast, leaders must have the ability to swap AI models as a core principle. Companies should abstract model calls behind a thin layer, while versioning prompts and evaluation harnesses so new models can drop in overnight. The ability to swap horses mid-race may be the competitive advantage necessary to win in a market today.

AI for leaders

Technology choices are leadership choices. Who decides what to automate? Which ethical red lines are immovable? How do we protect every human who works with us? Adopting AI is a leadership challenge that can’t be delegated to consultants or individual contributors. How we implement AI now will define the future successes and failures of the business world. It’s a challenge that must be driven by thoughtful leadership. Every leader must dive in and deeply understand the AI landscape and figure out how best to enable their teams to build the companies of tomorrow.